Cecilia. Villa Massimo Rome

1997-1998

Roma-Termini, Therese looks out of the window of the train at the hurly-burly among the people on the platform, pushing trolleys of luggage to and fro like ants, talking in loud voices and wildly gesticulating. She finds it hard to believe that she has already arrived in Rome. This time her soul would probably have rather travelled by coach and four, for since her experiences by the oaks and on the journey here, forgotten images of her childhood have been constantly appearing, and she would have liked more time to view them. When the train went through a tunnel there was a musty smell, like damp stone covered in moss. This smell reminded her of the small church in the village where she grew up. The modest church with its large Gothic windows through which the wind blew, with its benches painted pale blue and the wooden panelling outlined in colour, giving the church a grace Therese had always found attractive - by contrast to the huge eye of the Trinity commanding her reverence from the top of the altar. She spent as much time as possible in this church. Her older brother was a bell-ringer; each evening, before the services, at weddings, christenings or funerals he would heave down the long ropes hanging from the bells, making them clang. Therese found it a gruesome adventure to climb up the church tower, to be eyed suspiciously by the bats disturbed in their sleep and to feel the vibration of the bells in the old beams. She was proud of the fact that she was allowed to climb up there with her brother. Girls were supposed to play with dolls. She was far more interested in the scraps between the gangs of lads in the village, upper village against middle or lower village; the boys from the middle of the village, her brother among them, were usually the strongest. Therese had always wanted to fight too, and suggested that they could stage the battle of the Teutons against the Romans, but the village lads wouldn't listen. She was even teased for her idea, which was probably because no one took the history teacher who described the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest seriously, and they all enjoyed imitating him. "You are Germans, and the battle in the Teutoburg Forest is part of your history!" That was the way the elderly gentleman would begin all his reports on the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest - obviously his favourite battle - which was fought over and over again in his history lessons.

In the year 9 A.D., rebellions broke out in various regions of Teutonia, which served to scatter the Roman forces to a number of different places. Varus did not take this seriously, despite warnings, so that Herman and his fellow conspirators succeeded in fragmenting the Roman army. Close to the source of the Lippe, after a long and difficult march through marshes and woods, Varus suddenly found himself trapped in a valley surrounded by hills, all occupied by Teutonic warriors.

By contrast to all the other pupils, Therese did not find the history teacher's story uninteresting. She listened carefully, and afterwards she went - as she always did when she wanted to talk about something which she could share with no one - to the oaks in the field. The oaks had become her silent friends and allies, and she could tell them everything. In the attic of her parents' house, Therese made a very important find. She dug out an old edition of a Brockhaus Encyclopaedia and in it she found a text about Herman, lat. Arminius, the son of the Cheruscan prince, Sigimir.

After Herman had completed his education in Rome, he was elevated to knighthood and employed in the army of Augustus. But neither this patronage nor the magic of education made him unfaithful to his memories or to the gods of his own country. Educated in the Roman school, he learned to overcome Rome in Rome. Herman was convinced that raw Teutonic courage was insufficient to defeat Roman warcraft in battle, and so he resorted to cunning.

It was difficult for Therese to read in the old lexicon, for the edition was from 1834 and therefore printed in the old German alphabet. With considerable effort, she puzzled together letter after letter, copying out the description of the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest. At that time Therese always noted down everything which was important to her and read it out to the oaks. To do so she leant on the trunk of the oak which was farthest away, near the wood, so that she could be sure not to be discovered by anyone.

After Herman had fought and won freedom for his country, he destroyed the Romans' fortresses by the Elbe, the Weser and the Rhine and made every effort to develop the Teutons' fighting spirit. But Herman was soon compelled to fight against his own brothers - among them Segestes, the chief of a mighty tribe, whose daughter Herman had abducted. Segestes called for the aid of the Romans, and soon a Roman army appeared under Germanicus, preserving him from downfall. Amongst the prisoners who fell into Roman hands was Herman's wife Tusnelda. When she was presented to Germanicus, her conduct and bearing was worthy of her husband, Tacitus reports that she bore her pain in silence, resorting to neither tears nor pleas, she kept her arms folded and her eyes upon the body which bore the son of Teutonia's liberator.

Therese had always managed to read up to this point. But then huge tears began to run down her cheeks and her eyes had long dimmed over. She leant closer to the trunk of the oak and felt the warmth of the bark and the velvet moss upon it in the soft light of the evening sun.

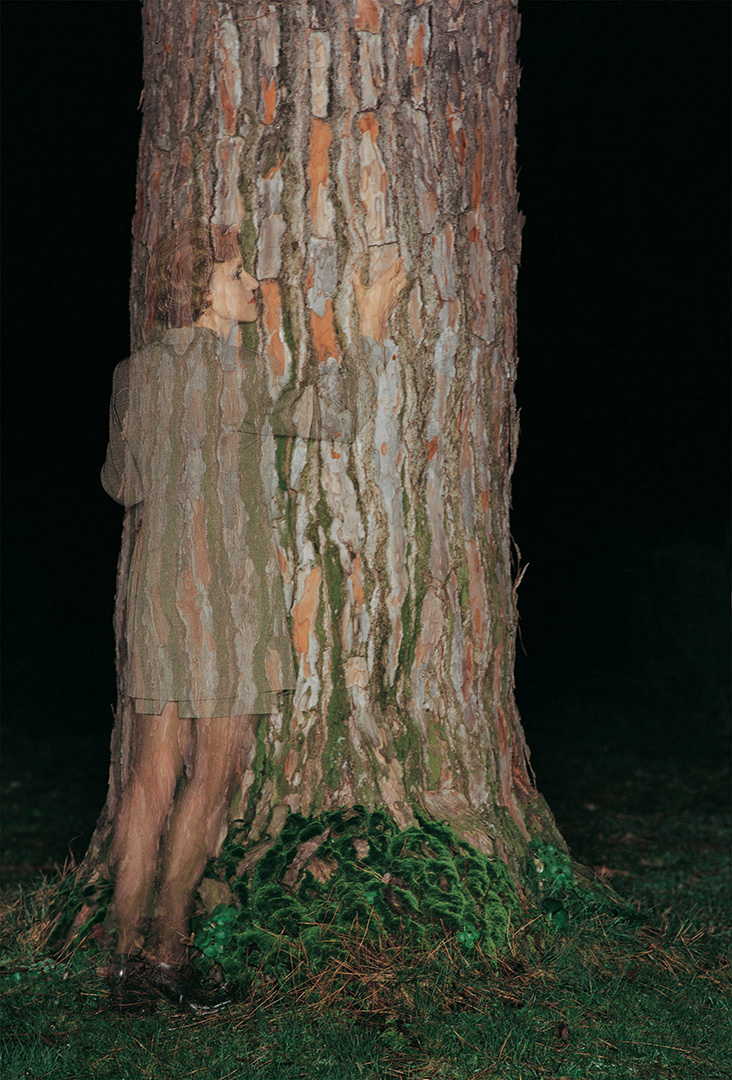

Shortly before her journey to Rome, Therese received an invitation to a class reunion in her home village. She was uncertain whether she should go. On the one hand, she had so much work to complete before the journey, on the other hand, she was curious to find out what her old schoolfriends were doing now and what it would be like to meet them after 20 years. When she had finally decided to go to the reunion, she began to feel a strange sensation at the pit of her stomach. She arrived at the village where she had grown up and gone to school far too early. Many things had changed in this village, but on the other hand she had the feeling - as she had done then - that time stood still here. She drove past her parents' old house, it was unoccupied, inhospitable and crumbling. For the first time Therese regretted not having saved the treasures which lay in the huge attic. That is, she would like to have the old edition of Brockhaus, the Universal German Encyclopaedia for the Educated Classes of 1834. When she thought about it, she remembered how she had copied out the text on the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest to read it out to the oaks. Deep in thought, she had quite subconsciously arrived at "her" oaks, which stood together beyond the village in an open field. She got out of the car and stomped over the heavy black field to the trees. The last warm rays of sun made the oaks shine golden and reddish, the trunks were warm and soft and more grown over with moss than they had been when Therese used to sit by them so often. She leant on the oak which stood furthest from the houses once more, so that she would not be visible if anyone came along the path from the village. Immediately Therese felt at home and protected and relished this feeling, only becoming aware now of how much she had missed it over the years. It seemed to her as if the bark of the oak opened up a little to absorb her, or to embrace her. Therese sat there without moving and allowed her thoughts and memories free rein. She remembered the text from the encyclopaedia almost word for word.

When the main army consisted of only three legions and the troops Herman had won over for his plot, the revolt among the Teutons became more general. Meanwhile, Herman and his friends, who were trusted by Varus and had access to his council, increasingly demonstrated apparent devotion to duty and pressed Varus to advance bravely towards the rebels and attack them. In vain, Segestes repeated his warnings; every day the Roman army left the Rhine further behind it, straying deeper into the areas where a pernicious trap had been set.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Therese slowly began to lose a sense of self and of the ground beneath her. Previously unknown images appeared before her eyes.

Tusnelda. When she was presented to Germanicus, her conduct and bearing was worthy of her husband, Tacitus reports that she bore her pain in silence, resorting to neither tears nor pleas.

Tears flowed over Therese's face, a profound pain she had never felt before appeared to be tearing her heart in two. The earth began to rock, or her whole body was rocking, and she felt as if she, together with the oak, were being flung into the air by a tornado. She leant firmly against the oak, clawing her hands into the bark and shouted: "I am Tusnelda, I am Tusnelda!" After this she sank onto the soft grass, her knees trembling. She felt liberated. Slowly, timidly this time, her lips formed the sentence once more: "I am Tusnelda". Therese felt the blood coursing through her veins, she was hot and at the same time a shiver ran down her spine. What had happened? But Therese's mind seemed empty, no past, no future, just here and now and a sense of weightlessness. A state unfamiliar to her. Slowly certain thoughts crept back, considerations of what was and what would be. Therese began to feel cold and noticed that night had fallen. She looked at her watch and had something of a shock. Then she had to smile, for the class reunion would surely be over by now - only Rome remained, and Tusnelda wanted to see Rome at last!

Marie-Luise Leupold: Tacitus reports, Text from the catalogue CECILIA; Villa Massimo Rom, 1998

Solo exhibitions

2003 / 2004

Die Vergangenheit hat erst begonnen. Szenische Photographien 1983-99 (Retrospective) Kunst und Medienzentrum Berlin-Adlershof; Kunstmuseum Moritzburg Halle/Saale; Städtische Galerie Iserlohn and Kunstverein Ahlen with Stiftung Künstlerdorf Schöppingen, Alte Feuerwache Fotogalerie Mannheim; Kunsthalle Erfurt

1997

Il mondo delle donne, Academia Tedesca, Villa Massimo Roma

Group exhibitions

2011

Rom sehen und sterben... Perspektiven auf die Ewige Stadt 1500-2011 Kunsthalle Erfurt

Publications

Leupold, M., Immisch, T., Kaufhold, E. and Stremmel, K., 2003. Die Vergangenheit hat erst begonnen. Szenische Photographien. 1st ed. Köln: Schaden.

Leupold, M. and Leupold, M-L., 1998. Cecilia. 1st ed. Rom: Deutsche Akademie Villa Massimo.

Public collection

Artothek Berlin

Privat collection

Facco-Bonetti

1997 Exhibition Il monde delle donne, Academie Tedesca Villa Massimo Roma